Double trouble

Already a multiple world champion on two wheels, John Surtees certainly set the cat amongst the pigeons when, in the 1960s, he decided to try his luck in Formula 1

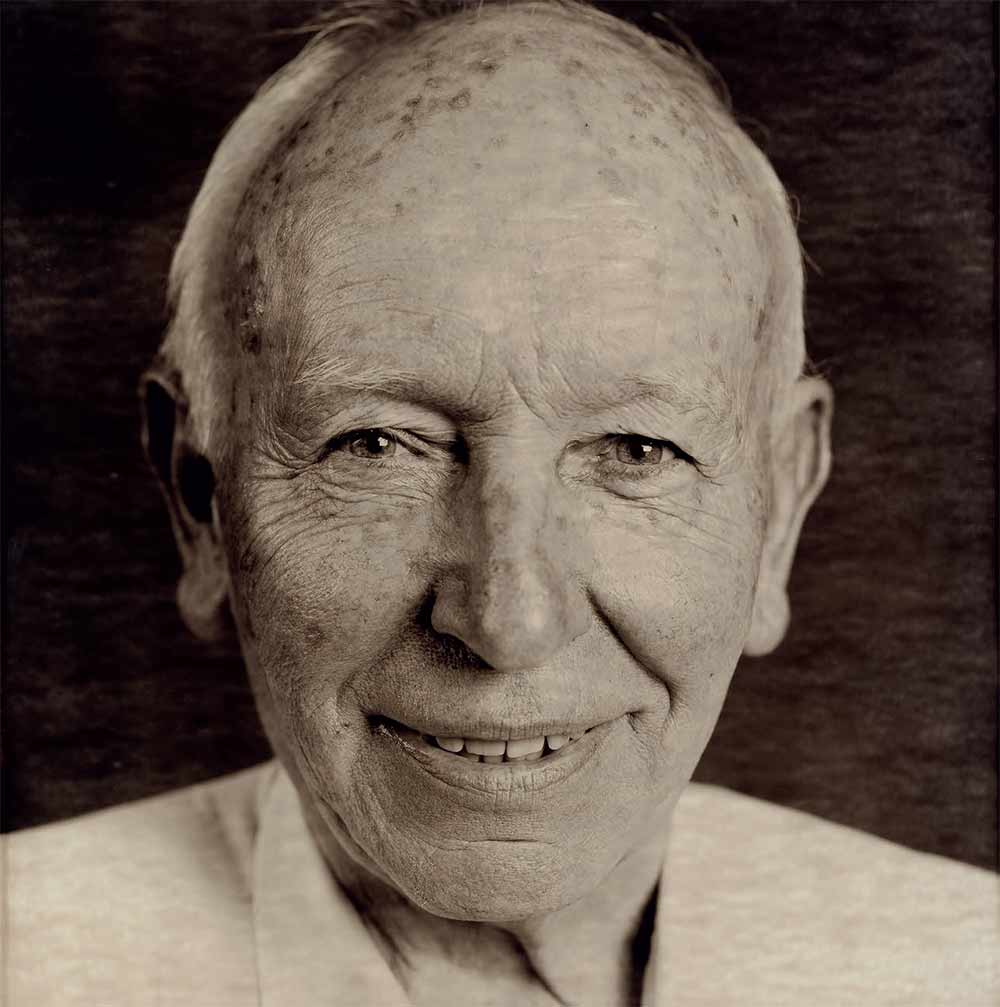

John Surtees is sat at a table in a bare room. The heater is on. His secretary said it had taken a long time to warm the place up. Some framed photos were stacked up against a wall. The one at the front of the pile was a beautiful portrait of his son Henry, fresh-faced and handsome, taken a short while before he was killed in a freak accident at Brands Hatch during a Formula 2 race in July 2009. He was 18.

Surtees holds a special place in motor sport history. He is still the only man ever to win the 500cc motorbike world championship and the Formula 1 world championship. No one else has come close. The latest to flirt with the idea is current 500cc maestro Valentino Rossi, but Rossi hasn’t even competed in an F1 race yet, let alone won a world title.

But there is nothing glamorous about Surtees’ office building, except the name. Monza House is a nondescript low-rise on an out-of-the-way industrial estate in Edenbridge, Kent. When Surtees set up his own F1 team in the 1970s, this place was its hub. But Team Surtees disappeared a long time ago, forced first into mediocrity and then extinction by funding problems. There is a feeling of melancholy about the place now, which is inevitable after the tragedy that has befallen Surtees and his family. Every time he mentions his boy, a racer of great potential, a young man of charm and grace and a son who was a never-ending joy to a father who had him late in life, Surtees’ red-rimmed eyes well with tears. “I never believed for a moment I would lose my son,” he says.

Surtees, 76, is all too aware of the grim irony of it all: he lived through the 1960s when F1 drivers died around him every year and at almost every race, when gravel traps were foreign concepts and cockpit safety was primitive and yet his son was taken away from him in an age when so much has been done to improve the driver’s chances of survival in an accident. “When you look at the conditions I raced in, it all looks terribly fragile,” Surtees says, “but at the time, you believed you were driving state-of-the-art cars. In hindsight, you realise they were lethal machines. When I first joined Ferrari, I went to a place like the Nürburgring where the car would jump and the chassis would flex so the fuel tank would leak in a number of places. In 1963, when I won my first Grand Prix there, the tank had leaked and my overalls were soaked in petrol.

Surtees (standing) in discussion with a group including Jackie Stewart (seated, first left) and Graham Hill (third right) at Spa Francorchamps in Belgium in June 1966.

“But we lived in a different age. If the fighter pilots of today were put into a World War II aircraft, they might have second thoughts about it. But it was a question of what was available at the time. For certain, the 1960s were a little more dangerous than other decades. The cars were technically more efficient than the type of cars that had raced in the Fifties, but the engineering was nowhere near as good. You used bits of Triumph Herald uprights to build Formula 1 cars and that was all a little bit marginal. You had these very small emerging companies coming along and their concepts were more efficient but the safety did not keep up with them.”

“When you look at the conditions I raced in, it all looks terribly fragile, but at the time, you believed you were driving state-of-the-art cars. In hindsight, you realise they were lethal machines”

There is another irony about Surtees’ career. Despite his astonishing achievements, his feat of versatility that has never been matched and which would have made him a superstar beyond compare had he been racing today, he was never quite granted the same respect afforded to the other great British racers of his generation. He won four 500cc world titles in the late 1950s and the F1 title in 1964 with Ferrari. In 1960, he won the 500cc title while racing Formula 1 at the same time. He should have been the most famous of them all, but it often feels as though he is the forgotten man of F1.

In contrast, the legend of his rivals has endured. There are many who believe Jim Clark was the best ever, a man whose honours would have outstripped everyone’s had he not been killed at Hockenheim in 1968. Jackie Stewart is revered as a man who won the title three times, who campaigned tirelessly for driver safety and is still valued as an ambassador by blue-chip companies. Graham Hill, who Surtees pipped to the drivers’ title in 1964, is remembered as the ultimate gentleman racer, the man who drank the night away before a race and jumped in the car the next morning and drove it to the chequered flag.

Surtees, a charming, gentle, avuncular man now, long ago learned to accept this version of history, even though he disputes its veracity. “I was always quicker than Jimmy in any similar car we drove so that was my main satisfaction,” he said. He blames his status as an outsider for the fact that he never got the credit he deserved. Some people in F1, he said, rival drivers and journalists, were always suspicious of him because he came straight into Formula 1 from bikes without serving an apprenticeship. He was never a politician, either. Far too nice for that. That cost him, too.

“Some of the press had not liked the fact I had come from motorcycling and was immediately challenging for a podium without ever having done any groundwork,” Surtees said. “It got to me a bit that people were niggling away at me. I had a call from Innes Ireland after I had been offered his drive at Lotus when I first switched from bikes and he was yelling at me about my stealing his drive and how he had a contract. In hindsight, I should have been more of a Senna or a Stewart and just told him to bugger off. But I was a bit sensitive about it. Innes was a great character and he must have felt a bit like Fernando Alonso when Lewis Hamilton arrived at McLaren. It was all right for one of the establishment to beat him but because it was someone from bikes, that was worse.”

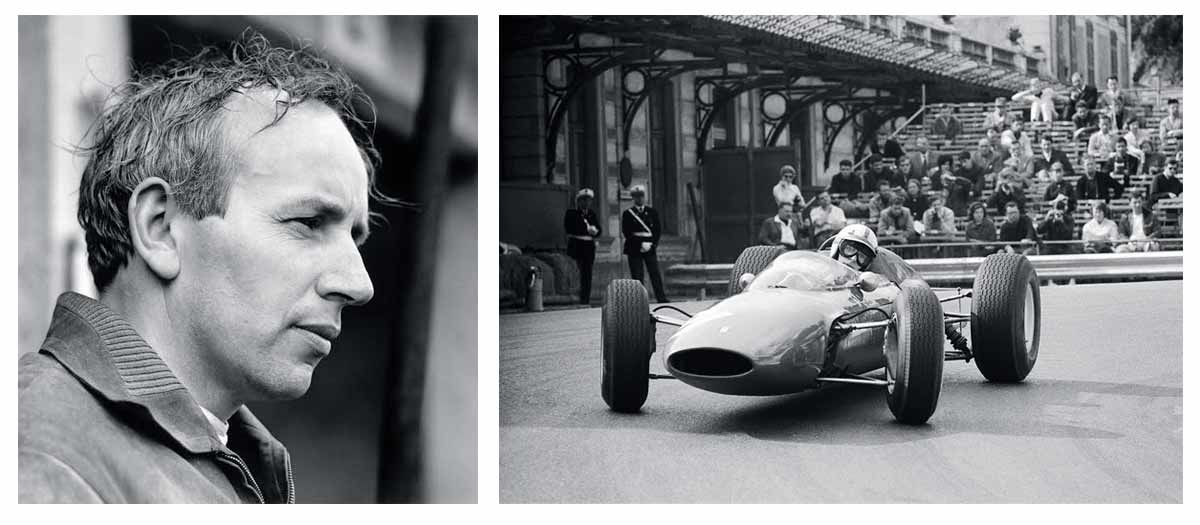

Despite retiring in three of his first four races, including the season-opening Monaco Grand Prix, Surtees won the 1964 world championship by a single point from compatriot Graham Hill.

“Some of the press had not liked the fact I had come from motorcycling and was immediately challenging for a podium without ever having done any groundwork,” Surtees said. “It got to me a bit that people were niggling away at me. I had a call from Innes Ireland after I had been offered his drive at Lotus when I first switched from bikes and he was yelling at me about my stealing his drive and how he had a contract. In hindsight, I should have been more of a Senna or a Stewart and just told him to bugger off. But I was a bit sensitive about it. Innes was a great character and he must have felt a bit like Fernando Alonso when Lewis Hamilton arrived at McLaren. It was all right for one of the establishment to beat him but because it was someone from bikes, that was worse.”

Surtees, of course, was not just someone from bikes. He won the 500cc world title three times in succession, four altogether, riding for MV Agusta. He also won the 350cc title three times and continued to prepare and ride his own bikes as a private entrant. “In 1959, I had machines of my own which I had kept working on,” Surtees said. “I loved working and developing them. I had some Nortons and rode them at races. The Italian press picked up on this and wrote some stories about how I didn’t need an Agusta to win. The team said this had to stop, but I didn’t want to do just 10 or 11 races a year. I loved my racing but they said I had to be looked on as pure MV Agusta. I couldn’t really argue because it was in my contract. So I thought maybe I could drive a car. There was nothing in my contract that stopped me driving a car. I thought I’d get my extra racing in that way.”

“My car side is tinged with a certain anger that I made some mistakes. I excuse myself partly in that I was dropped in the deep end because I knew nobody when I arrived in Formula One. The only thing I had in my favour was that I was as quick as anybody”

Surtees was not short of offers. He went to a Sportsman of the Year dinner in Park Lane in 1958 and found himself on a table with Mike Hawthorn, who had just won the F1 title. Also there were Reg Parnell, the team manager at Aston Martin, and Tony Vandervell, the Vanwall boss. “You want to try driving a car,” Hawthorn told Surtees. “They stand up easier.” Vandervell and Parnell pressed him more seriously and although he waved them away, an idea had taken hold. He tested at Goodwood and, encouraged by Colin Chapman, entered his first F1 races in a Lotus in 1960.

His relationship with Lotus and Chapman, the team’s charismatic boss, ended when Surtees walked away from the team because he did not want to become embroiled in a political dispute with Innes Ireland. Eventually, he moved to Ferrari, where he had to deal with the frustration that came with the Italian team pouring most of its energies each season into sports cars, at least until the Le Mans 24 Hours race had been run. In 1964, Surtees had a terrible start to the season, retiring in three of the first four races, but after Le Mans things improved. By finishing second at the Mexico Grand Prix, the final race of the season, he beat Hill and Clark to the title.

But Surtees fell out with Ferrari over the team’s internal politicking a couple of years later and threw himself into a new project with Honda. Then, when that failed to yield the results he had hoped for, he set up his own team in 1970. He poured practically every penny he had ever earned from motor racing into Team Surtees. Sadly, he was always short of funding and the team folded in 1978.

No one has got close to winning world titles on bikes and in cars since, but Surtees thinks it could still be done. “I changed at 26 years old,” he said. “Often people have left it too late and carried on with their careers to a point where they were over the hill. We all have performance curves. I would have continued to get better as a motorcyclist.

I wasn’t over the hill or past my peak. That meant that I was able to be fully adaptable when I sat in a car. Rossi got in a car and went well in testing, but he hasn’t got into a race car because he wasn’t quick enough. There can’t be any other reason. I wouldn’t rule out someone doing it because you have got so many aids. When Rossi sat in Michael Schumacher’s Ferrari, he would have had all the telemetry and would have known where Schumacher did this or that. He didn’t have to learn it. It was there for the taking.”

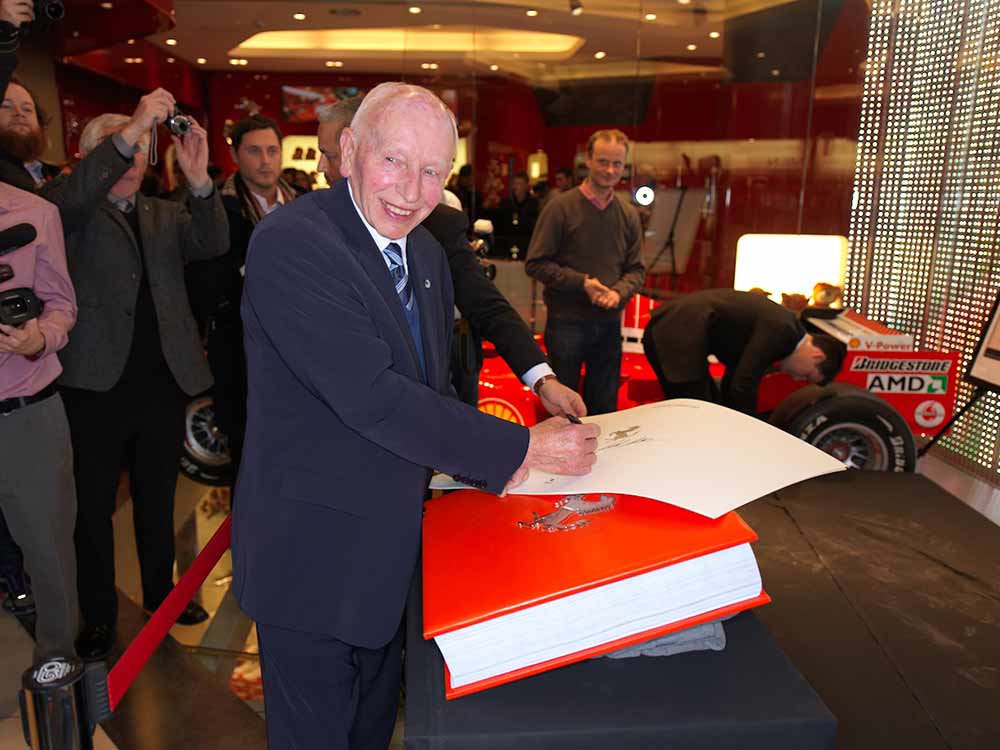

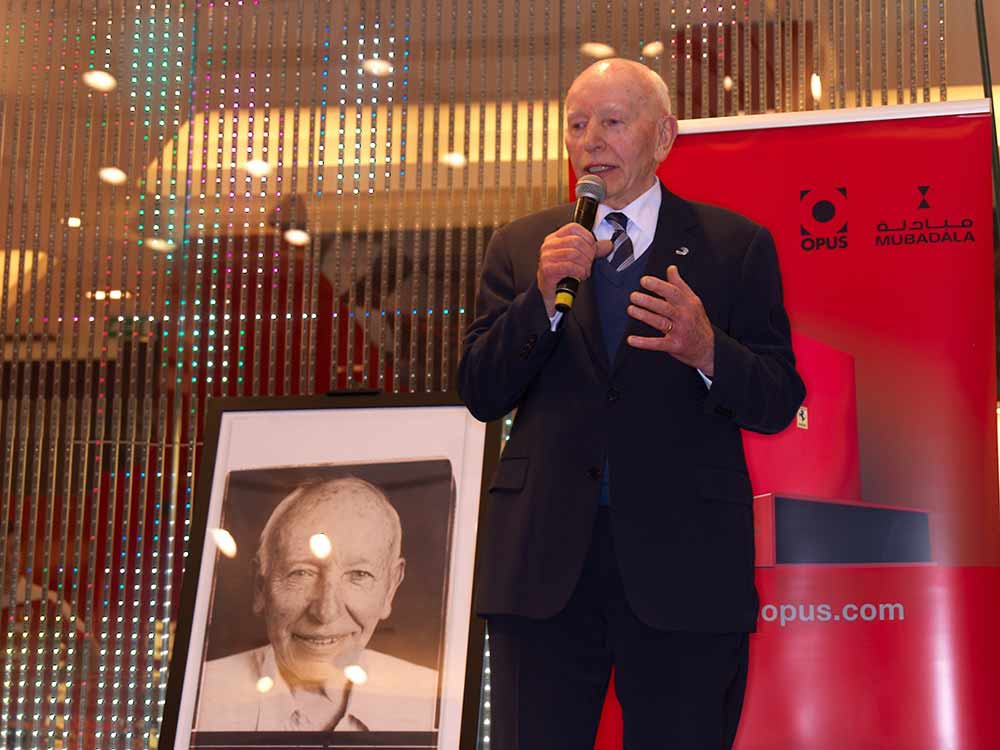

John Surtees was an ambassador for the F1, Ferrari and Le Mans Opuses.

So for a man who was master of both disciplines, who achieved the greatest glory on two wheels and on four, which did he enjoy the most? Which was his true calling? “When I think back to my F1 career,” Surtees said, “my enthusiasm threw me off. As a racing driver, I should have taken more care of sitting myself in seats that were competitive. In terms of successes on paper, I did not take enough care or a cold enough analytical approach to what I drove. Okay, I always left a team stronger than it started. I had no worries about competing with anybody, but you have to remember that some of these people had worked so hard at promoting themselves and projecting themselves that it was their lifetime’s work. And I always had quite a lot of other interests in things which may not have been the most money-making but brought me a lot of satisfaction.

“If I take the overall package and look at it over a lifetime, I have to say I enjoyed bikes more than cars because I made more of the right decisions. My car side is tinged with a certain anger that I made some mistakes. I excuse myself partly in that I was dropped in the deep end because I knew nobody when I arrived in Formula 1. I was a totally new boy and I had no apprenticeship whatsoever. The only thing I had in my favour was that I was as quick as anybody.

“I should probably have gone to Colin Chapman in later years and said sorry for what had happened at Lotus and asked him to make it up and do what we should have done earlier. But I got carried away with the idea of making the Honda work and just as we thought it was going to come to fruition, it got nipped in the bud because of events in Tokyo. So it was following one or two lost causes that cost me.

It was disappointing. But at the same time, I recently lost my son and I got a very nice letter from Mrs Honda saying how upset she was because I was still one of the family. Ferrari sent my original chief mechanic at Ferrari over for

the funeral. It is nice to think the teams I have driven for still have that respect. That counts for more than anything.”

This article was originally featured in The Official Formula 1 Opus.