When Bernie

Met Max

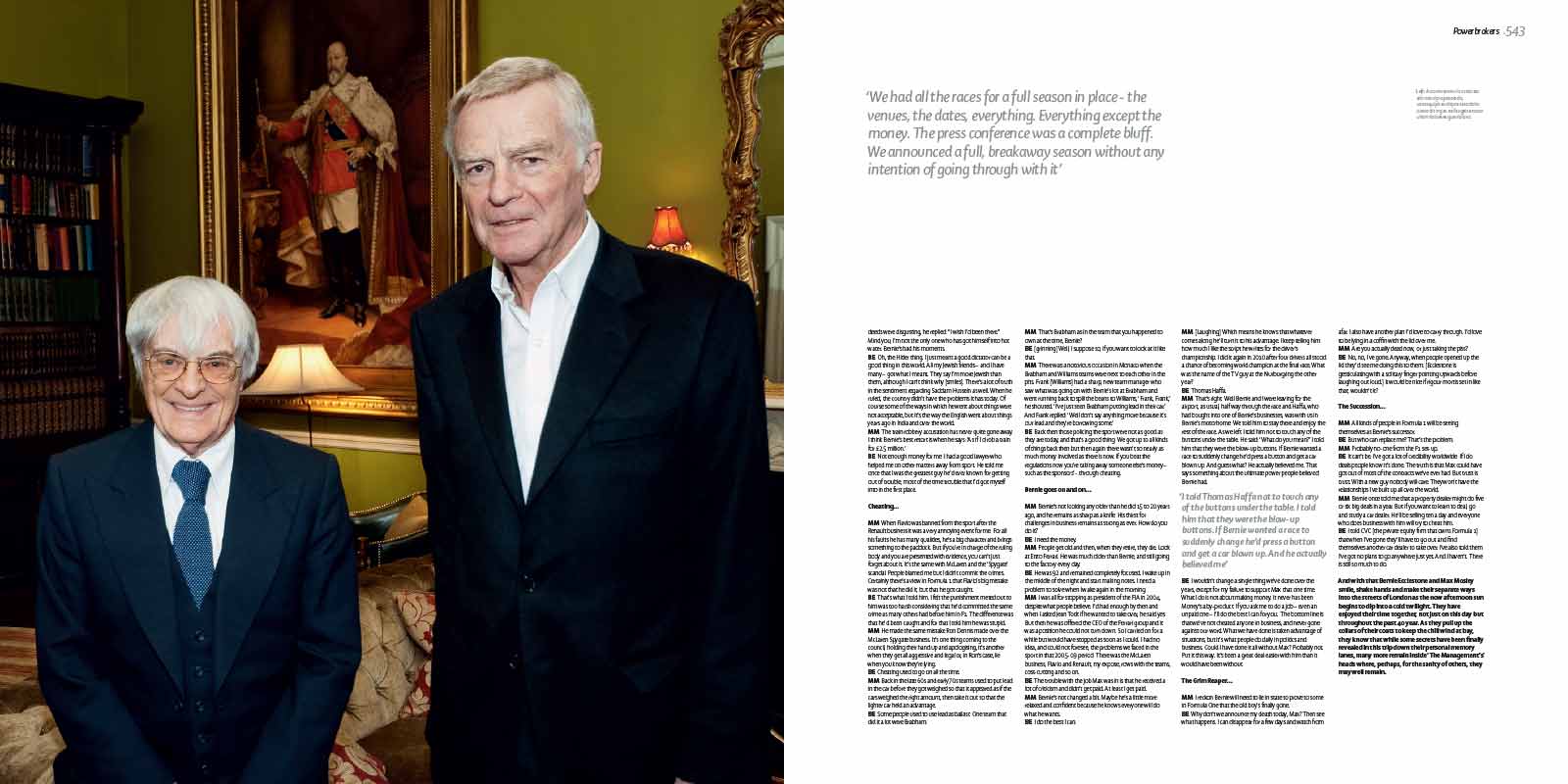

Interview with Bernie Ecclestone & Max Moseley

Originally featured in The Official Formula 1 Opus

When old friends and long-term professional associates Bernie Ecclestone and Max Mosley came together on a cold autumn morning in London to reminisce over their 40 years together at the helm of Formula 1, The Official F1 Opus was there to eavesdrop. Over the next two hours or so, an 80-year-old and a 70-year-old laughed and cried at the tricks they pulled, the scrapes they got into and emerged from, almost unscathed, and the manner in which they – The Management – hauled the sport into the 21st century.

The following is an illuminating and wholly exclusive insight into how the pair managed to pull it off and get away with it, including a string of jaw-dropping revelations that go a long way to explaining the mentalities of a former car dealer turned most powerful figure in Formula 1, and a lawyer who went along for the ride and ended up president of the sport’s governing body.

Early Days…

Max Mosley: The first time I laid eyes on Bernie was at a Formula 2 race. I didn’t speak to him, just looked at this guy in a leather jacket with a huge reputation in the racing world. He had an aura of being a successful businessman. This was in the late 60s, but the first time we spoke was at a meeting of the F1 Constructors and Entrants Association in 1971. Bernie had bought Brabham and I had March so we both attended, sitting opposite each other. As the meeting went on it was obvious to me that Bernie was in a different league from the rest just by the odd things he’d say. By the end of the meet we’d managed to wind up sitting next to each other.

Bernie Ecclestone: And that’s pretty much how it stayed for the next 40 years. I didn’t know he was involved in March. I thought Max was still a racing driver, and a bloody good one as well. He was quick. I thought he was the first Schumacher.

MM: I was OK. You had to wait a bit for me to come past you but I did in the end.

BE: Max was a genuine amateur racing driver at a time, even then, when some were already a bit more than that. It was the same with my racing aspirations. I was first and foremost a businessman. The racing was a hobby.

MM: Although neither of us made it as racing drivers I don’t see it as a failure. Far from it. I don’t think we could have done what we have in motorsport unless we’d fundamentally been racers. It’s always been said that Bernie and I only knew about business. Well, we’ve both done that thing where it’s pissing down with rain at Mallory Park and we’re looking for a nut in the mud with nothing to gain except your love of the sport.

BE: We both served our apprentices as racing drivers. It put us in good stead.

MM: At that first meeting there were people there like Jack Brabham and I have to say I wasn’t too impressed. The governing body and the race organisers were one and the same – which was illegal even then. They never trusted each other so they went everywhere together in case one of them shafted the other. They hated me because they never thought we’d build a car at March, let alone race it. I couldn’t believe a major sport was run in such an amateur way. So, when Bernie appeared, it was like a breath of fresh air. They were a bit frightened of him, a bit nervous. [Laughing]. It was said that Bernie could walk into a showroom full of cars and give an accurate price on them all within a couple of minutes. People came from all over England to deal with him. Is that story about you true, Bernie?

BE: Yep, 100 per cent. Formula 1 was a bit of a joke back in the early 70s. It needed sorting out and that’s what Max and I did. I was the dealer and he was the one who made sure what I did was honest and reputable.

MM: We started negotiations with the governing body. When it came time for both sides to consult I recall suggesting we stepped outside to give them some privacy, but Bernie insisted it was the other way round, and that we stayed in the room and they left. As soon they’d gone, Bernie was in to the waste paper baskets examining their screwed-up notes. He’d say to me: ‘You know Max, your problem is that you always want everything absolutely clear. Sometimes it’s better when it’s not clear.’ Bernie was, and has always been, a dealer whereas I was just a simple lawyer. I was just happy to have come across someone who functioned in a way I couldn’t.

BE: Max didn’t believe people were devious. The world’s devious, not just motorsport. Politics and business are far more devious than sport. But Max has always been a bloody good lawyer. I’ve said a million times he’d have made a good prime minister. I even told Margaret Thatcher. Max could have done almost anything he wanted to.

Big balls and threats with guns…

BE: Anyone who says they’d planned the past three years, let alone ten, is talking rubbish. The world changes very quickly. We played high-powered poker with, early on, not too much money to back it up.

MM: Bernie’s a master tactician, the best I’ve ever known. He’s never had to worry about planning or strategy because he’ll turn whatever comes his way to his advantage. Bernie’s talents were ideal for the world we came to live in.

BE: Well Max has got big balls as well. When people challenged the pair of us they didn’t really have much of a chance. The bottom line was that the FISA [the governing body, now called FIA] used to terrorise people. They tried to terrorise us at first, with not a great deal of success.

MM: There was a traffic policeman in Italy who stopped me and Bernie in Monza. He was clearly pissed and I told him that I’d had enough talking to him and that Bernie and I were going to a restaurant where we would call the proper police. We started walking away and the policeman pulled a gun on us and shouted ‘Stop!’ We ignored him and carried on walking. We heard the cocking of the gun and the word ‘Stop!’ again, this time shouted out even louder. Again we just carried on walking. Then he fired the gun and Bernie swears he heard the bullet fizz past us. We still carried on walking, straight into the restaurant where Bernie called the police chief who turned up, apologised and promised the pissed, gun-happy policeman would be sent to Sardinia. That sheds light on our mentality. We don’t let anyone f*** with us.

BE: And to this day we see that police chief at Monza. We look after him for the race. Later, when Ronnie Peterson had his accident there the police tried to stop me from seeing what was wrong. The same chief pulled out his gun and pointed it at his fellow officers who were preventing me from making my way to the crash. It seems we had our own protection.

MM: Do you remember that meeting we had with Jean-Marie Balestre [former President of the FISA] and the World Council, Bernie? Jean-Marie started to make a grand speech which we were all supposed to listen to, but Bernie rose from his seat and started going round the room adjusting the pictures on the wall. Suddenly everyone stopped listening to him and started watching Bernie. It was very distracting.

BE: Yes, and do you recall Jean-Marie’s reaction? [Giggle].

MM: Yes [Laughing]. He was holding a pencil in both hands and he was so angry he snapped it into two pieces. I found it all so funny that I had to knock my papers to the floor and then stay under the table supposedly gathering them up until I had myself under control. It was one of Bernie’s biggest criticisms of me that when we had something good going, I’d start laughing. I couldn’t keep a straight face whenever Bernie started to take the piss.

BE: He’d start to laugh and spoil it! [Laughing].

MM: Once Bernie sent me down to Zimbabwe just after Mugabe had taken over power to see if there was a possible race to be staged there. When I was in Harare the minister of external affairs asked me: ‘Mr Mosley, are you related to the great Sir Oswald Mosley?’ which was a question, let alone the phrasing of it, that I’d never heard in ten years’ involvement in motorsport. Indeed, when I was racing there was an occasion when I saw my name up on the practice times and overheard someone say: ‘Mosley, Mosley. He must be related to Alf Mosley, the coach builder in Leicester.’

BE: It was clear a race couldn’t be done but we decided to get Jean-Marie in on the act and had a bet with him that he couldn’t announce a new race in the calendar in Zimbabwe and keep a straight face. Jean-Marie was determined to do it at a press conference, but the closer he got to the actual words the more he’d start to laugh. He wasn’t too bad, Jean-Marie. He was all right.

Laying the foundations for control…

MM: After I decided not to carry on pursuing a career in politics, I had a word with Bernie and he arranged a dinner with Balestre in Cannes. There he told him that I would be the right person to represent the car industry on the World Council. All Balestre’s instincts were telling him this was not wise but, with me sitting there, he couldn’t say no. So he agreed. There were two other candidates for this position and the people who voted were representatives of the car industry. The votes went something like 13 for one of them, 9 for the other, and 2 for me. Two days later Balestre held a World Council meeting and told those assembled that it was for the council to decide. That’s how I got in.

BE: Unanimously, wasn’t it? [Laughing, again].

MM: Yes, it was. At the time Balestre was being sued by Peugeot, headed up, ironically, by Jean Todt (who went on to become President of the FIA). Even though Peugeot’s case was correct, I managed to get the Council to stick with Balestre. When I told him the happy news Balestre embraced me but added: ‘I’m worried about Bernie, though.’ I told him that in France if you have a problem you use the guillotine but in England you bring them into the establishment and control them that way. So Bernie became an FIA vice-president. That’s when we really started to make moves.

BE: That was always one of Max’s greatest strengths. Legally he could make anything happen.

MM: The first pirate event, if you want to call it that, started in Spain. There had been a row over drivers’ licences which had been taken away. We had all the teams on our side except the grandees (Ferrari, Alfa Romeo). We said we’d race in any case and with the help of the head of the Spanish Motor Club we had all the FISA officials marched out of the circuit at gunpoint by the Guardia Civil. We held all the cards.

BE: And that’s because of the meeting we had with Balestre, Max, and the list.

MM: Oh yes. Balestre could see the way it was going and wanted to make peace with us. He appeared at my door at seven in the morning, still in his pyjamas, saying [Mosley puts on a French accent]: ‘We have to meet, we have to meet.’ He was already demoralised because he’d become so animated in a conversation with the team manager of Ferrari earlier that morning that he’d forgotten about his bath water and it had overflowed, drenching half his room and the hotel floor. We met around a table and Bernie spotted a list of the people who were on Balestre’s side. He leant across to me and said: ‘You tip the papers over and I’ll nick the list.’

BE: Jean-Marie’s English was terrible so he didn’t understand what I’d just said to Max.

MM: So I ‘accidentally’ sent all the papers flying and as Bernie got on the floor to help Balestre gather them up, he grabbed the list. Then Jean-Marie started saying: ‘My list, where is my list.’ I knew exactly where his list was – it was shoved in Bernie’s jacket pocket.

BE: Thankfully Max managed not to laugh this time, which was a bit of a first.

MM: So we ran the race, which the FISA declared as non-championship. On the Monday there was a big FISA general assembly meeting in Athens. Bernie declared at seven o’clock on the Sunday evening – from the race circuit – that we had to get to this Athens meeting. I had no idea how we could do this, but we went to Madrid airport and when we found that there were no flights, Bernie somehow discovered an American pilot with a private jet who was flying to Riyadh. I’ll never know how he did this, but he persuaded the American to take us to Athens for free.

BE: I explained to him that Athens was on his way to Riyadh.

MM: You should have seen the World Council members’ faces when we turned up at nine the next morning at the Athens meeting. You could have cut the atmosphere with a knife. During the meeting Balestre was constantly sending telexes to his Paris offices. Bernie had an Italian journalist who had made friends with the girl who operated the telex machine. It meant that we were able to see every telex.

BE: Some of the telexes Balestre sent to Paris that didn’t suit us, we kept. And those that came from Paris that didn’t suit us disappeared. A lot of it was legal advice. Balestre saw nothing we didn’t want him to. He never knew, of course, and we never told anyone about it either… until now.

Painting cows and winning the war…

MM: Bernie decided to create a finance and general purposes committee, an idea he nicked from the trades unions. Colin Chapman, Teddy Mayer and myself were on the committee and we were eating dinner one night in Kitzbühel when we noticed that there was a picture of a cow on the wall and people were painting on it. Colin asked the waitress what was going on and she explained that there was a siege here and when the townsfolk ran out of food they didn’t want those besieging them to find out, so they paraded a cow in full view of them each day, but painted in different colours. Colin’s eyes opened wide and he shouted: ‘That’s it. We’ll put on a race to give the impression we have some money.’ Well, we were all enthused by this idea and rushed up to my room to phone Bernie and tell him all about the painted cow. Do you remember what your response was, Bernie?

BE: I do. I said: ‘You’re all pissed.’

MM: So we staged a race in South Africa, which caused all sorts of panic. Goodyear, the tyre company, said they were with us but couldn’t be seen to support a breakaway. Luckily Bernie had a business supplying tyres to lesser Formulae.

BE: Formula 3000.

MM: He had a warehouse full of Avon tyres so he had them flown down to Kyalami. Afterwards we held a press conference in the hotel on the Place de la Concorde, next to the FISA offices.

BE: We had all the races for a full season in place – the venues, the dates, everything. Everything except the money. The press conference was a complete bluff. We announced a full, breakaway season without any intention of going through with it. That led to the binding Concorde Agreement where we got the commercial and TV rights. I think Jean-Marie convinced himself he’d won because the FISA kept the rules and regulations. Deep down he knew he’d conceded too much, but reckoned that within four years everything would come back to him and he’d be able to get rid of us. I remember, when we reached agreement, Balestre suggested we didn’t announce it but instead made out we were still at war. He was such a good press man. He had no idea what I had just secured.

MM: In fairness obtaining the TV rights was not about making money, but attracting more sponsors to the sport through better and more TV coverage.

BE: The teams didn’t mind what I was making, only when we sold some of the business to CVC and others started to make some money. But one or two of them didn’t see the full picture. Ken Tyrrell, for exampe, would rather have had 90 per cent of 100 than 50 per cent of 500. Remember when we took off in the fog, Max?

MM: [Laughing] We’d got to Bologna airport after a meeting at Ferrari only to be told that our private jet couldn’t take off due to freezing fog, and that the airport had shut down. The fog was so bad that our driver couldn’t even find the airport. There was black ice on the runway and all the passengers had resigned themselves to sleeping rough in the terminal. Bernie asked Colin [Chapman] to go outside and persuade the pilot to fly the plane. Colin returned shaking his head, so then Bernie announced as it was so cold in the terminal he’d rather go and sit in the plane where it would be warmer. So we all traipsed over to the plane and sat inside. After a while Bernie suggested to the pilot that if he started an engine the plane would get warmer. A little later he said the second engine should be started for the same purpose. By this time, the penny had dropped with Colin and he suggested the pilot should taxi down the runway and take a look as everyone knows fog can quickly come and go.

BE: At that point all the people in the terminal were looking at us, pressing their noses up against the windows. I think I shouted out: ‘Look, they’ve all come to look at our shunt.’

MM: You could see two lights on the runway and if you could see four then it would be deemed good enough to fly. Bernie then proclaimed: ‘That’s it, I see four lights.’ So the pilot, who half an hour earlier was steadfastly refusing Colin’s pleas, took off and, 50 to 100 feet from the ground, the fog had gone. Now there’s an example of Bernie’s ability to talk people into doing something they know bloody well they shouldn’t.

Bernie’s one regret and a newspaper expose of Max…

BE: I was bad with Max over that. I didn’t support him over the News of the World business and I should have done. I let a friend down and I apologised to him at the FIA World Council meeting. I had so many people calling me saying we couldn’t have Max as the head of Formula 1’s governing body – teams, sponsors, media, the lot. I went against what I should have done. Max knows I’ve got big balls and I do what I like, so I should have stuck by him.

MM: My first reaction was that I wasn’t just going to resign. The FIA had elected me so I’d call a general assembly and if they told me I should go, then I would have done just that. Bernie advised me against this, telling me I’d lose and it would be humiliating for me, but I told him I wasn’t going without a fight. To be fair to Bernie everyone was on his back saying they couldn’t have someone that is a pervert running the FIA.

BE: Worse still, I had an argument with my ex [Slavica] over Max. It was her birthday and we were having a party for her on Flavio Briatore’s yacht and Max was coming along. I knew the press would be around so I asked Slavica to greet Max at the entrance with a big hug. Flavio told me we couldn’t do that because we had some big sponsors on the boat and they’d leave. I said to Max, better you don’t come. Slavica was very angry with me over that, and she was right to be.

MM: Jean Todt at Ferrari was 100 per cent behind me, so too was Luca [Ferrari CEO Luca di Montezemolo]. In fact, one of my biggest regrets about the whole episode was how it stopped my cost-capping scheme in Formula 1 from happening. We got the teams together in January ’08, and they all agreed on cutting costs except Ferrari. Between January and May we came up with a workable scheme to check expenditure, but then the News of the World report happened and I wanted to say to Ferrari that everyone else agreed with the cuts so we were going to do it, with or without their support. But when Ferrari became my biggest defenders and supporters I couldn’t go through with it. While everyone was calling for my head, Ferrari stuck by me. So the idea of cutting costs was put out to the long grass and that was the worst consequence.

BE: Yep, that’s one of two important things we wanted to happen that didn’t. The other was to introduce a drivers’ transfer scheme between teams, where they could be exchanged like footballers. The Old Man [Enzo Ferrari] was against it so it didn’t happen. A year later he was having trouble with Michele Alboreto and he told me: ‘You were right.’ The other was the cost-cutting. As for what Max actually got up to which got the News of the World so excited, I phoned him and said: ‘Max, in all the years we’ve worked together I’ve been to every single meeting you’ve ever suggested, every single meeting except this one, and I’m a little pissed off I wasn’t invited.’

MM: That’s exactly what Bernie said to me. In what was a difficult time it certainly made me laugh. Kimi [Raikkonen] said the same thing. When he was asked if he thought my deeds were disgusting, he replied: ‘I wish I’d been there.’ Mind you, I’m not the only one who has got himself into hot water. Bernie’s had his moments.

BE: Oh, the Hitler thing. I just meant a good dictator can be a good thing in this world. All my Jewish friends – and I have many – got what I meant. They say I’m more Jewish than them, although I can’t think why [smiles]. There’s a lot of truth in the sentiment regarding Saddam Hussein as well. When he ruled, the country didn’t have the problems it has today. Of course some of the ways in which he went about things were not acceptable, but it’s the way the English went about things years ago in India and over the world.

MM: The train robbery accusation has never quite gone away. I think Bernie’s best retort is when he says: ‘As if I’d rob a train for £2.5 million.’

BE: Not enough money for me. I had a good lawyer who helped me on other matters away from sport. He told me once that I was the greatest guy he’d ever known for getting out of trouble, most of the time trouble that I’d got myself into in the first place, mind…

Cheating…

MM: When Flavio was banned from the sport after the Renault business it was a very annoying event for me. For all his faults he has many qualities, he’s a big character and brings something to the paddock. But if you’re in charge of the ruling body and you are presented with evidence, you can’t just forget about it. It’s the same with McLaren and the ‘Spygate’ scandal. People blamed me but I didn’t commit the crimes. Certainly there’s a view in Formula 1 that Flavio’s big mistake was not that he did it, but that he got caught.

BE: That’s what I told him. I felt the punishment meted out to him was too harsh considering that others had committed the same crime as him before in F1. The difference was that he’d been caught and for that I told him he was stupid.

MM: He made the same mistake Ron Dennis made over the McLaren Spygate business. It’s one thing coming to the council, holding your hand up and apologising, it’s another when you get all aggressive and legal or, in Ron’s case, lie when you know they’re lying.

BE: Cheating used to go on all the time.

MM: Back in the late 60s and early 70s teams used to put lead in the car before they got weighed so that it appeared as if the cars weighed the right amount, then take it out so that the lighter car held an advantage.

BE: Some people used to use lead as ballast. One team that did it a lot were Brabham.

MM: That’s Brabham as in the team that you happened to own at the time, Bernie?

BE: [Grinning] Well, I suppose so, if you want to look at it like that.

MM: There was a notorious occasion in Monaco when the Brabham and Williams teams were next to each other in the pits. Frank [Williams] had a sharp, new team manager who saw what was going on with Bernie’s lot at Brabham and he quuickly went running back to spill the beans to Williams, ‘Frank, Frank,’ he shouted. ‘I’ve just seen Brabham putting lead in their car.’ And Frank replied: ‘Well don’t say anything more because it’s our lead and they’re borrowing some.’

BE: Back then those policing the sport were not as good as they are today, and that’s a good thing. We got up to all kinds of things back then but then again there wasn’t so nearly as much money involved as there is now. If you beat the regulations now you’re taking away someone else’s money – such as the sponsors’ – through cheating.

Bernie goes on and on…

MM: Bernie’s not looking any older than he did 15 to 20 years ago, and he remains as sharp as a knife too. His thirst for challenges in business remains as strong as ever. How do you do it?

BE: I need the money.

MM: People get old and then, when they retire, they die. Look at Enzo Ferrari. He was much older than Bernie, and still going to the factory every day.

BE: He was 92 and remained completely focused. I wake up in the middle of the night and start making notes about various things. I need a problem to solve when I wake again in the morning.

MM: I was all for stopping as president of the FIA in 2004, despite what people believe. I’d had enough by then and when I asked Jean Todt if he wanted to take over, he said yes. But then before it could happen he was offered the position of CEO of the Ferrari group and that was a job he could not turn down. So I carried on for a while but would have stopped as soon as I could. I had no idea, and could not foresee, the problems we faced in the sport in that 2005–09 period. There was the McLaren business, Flavio and Renault, my expos…, rows with the teams, cost-cutting and so on.

BE: The trouble with the job that Max was in is that he received a lot of criticism for some of his decisions and didn’t get paid. At least I get paid.

MM: Bernie’s not changed a bit. Maybe he’s a little more relaxed and confident because he knows everyone will do what he wants.

BE: I do the best I can.

MM: [Laughing] Which means he knows that whatever comes along he’ll turn it to his advantage. I keep telling him how much I like the script he writes for the driver’s championship. I said it to him again last season, in 2010, after four very different drivers all stood a chance of becoming world champion going into the final race of the year. What was the name of the television guy at the Nürburgring the other year?

BE: Thomas Haffa.

MM: That’s right. Well Bernie and I were leaving for the airport, as usual, half way through the race and Haffa, who had bought into one of Bernie’s businesses, was with us in Bernie’s motorhome. We told him he was very welcome to stay right where he was and enjoy the rest of the race. But then as we were leaving I told him not to touch any of the buttons under the table. He said: ‘What do you mean?’ I told him that they were the blow-up buttons. If Bernie wanted a race to suddenly change he’d press a button and get a car blown up. And guess what? He actually believed me. That says something about the ultimate power people believed Bernie had.

BE: I wouldn’t change a single thing we’ve done over the years, except for my failure to support Max that one time. What I do is not about making money. It never has been. Money’s a by-product. If you ask me to do a job – even an unpaid one – I’ll do the best I can for you. The bottom line is that we’ve not cheated anyone in business, and never gone against our word. What we have done is taken advantage of situations, but that’s what people do daily in politics and business. Could I have done it all without Max? Probably not. Put it this way. It’s been a great deal easier with him than it would have been without.

The Grim Reaper…

MM: I reckon Bernie will need to lie in state to prove to some in Formula One that the old boy’s finally gone.

BE: Why don’t we announce my death today, Max? Then see what happens. I can disappear for a few days and watch from afar. I also have another plan I’d love to carry through. I’d love to be lying in a coffin with the lid over me.

MM: Are you actually dead now, or just taking the piss?

BE: No, no, I’ve gone. Anyway, when people opened up the lid they’d see me doing this to them. [Ecclestone is gesticulating with a solitary finger pointing upwards before laughing out loud.] It would be nice if rigour mortis set in like that, wouldn’t it?

The succession…

MM: All kinds of people in Formula 1 will be seeing themselves as Bernie’s successor.

BE: But who can replace me? That’s the problem.

MM: Probably no-one from the F1 set-up.

BE: It can’t be. I’ve got a lot of credibility worldwide. If I do deals people know it’s done. The truth is that Max could have got out of most of the contracts we’ve ever had. But trust is trust. With a new guy nobody will care. They won’t have the relationships I’ve built up all over the world.

MM: Bernie once told me that a property dealer might do five or six big deals in a year. But if you want to learn to deal, go and study a car dealer. He’ll be selling ten a day and everyone who does business with him will try to cheat him.

BE: I told CVC [the private equity firm that owns Formula 1] that when I’ve gone they’ll have to go out and find themselves another car dealer to take over. I’ve also told them I’ve got no plans to go anywhere just yet. And I haven’t. There is still so much to do.

And with that Bernie Ecclestone and Max Mosley smile, shake hands and make their separate ways into the streets of London as the now afternoon sun begins to dip into a cold twilight. They have enjoyed their time together, not just on this day but throughout the past 40 year. As they pull up the collars of their coats to keep the chill wind at bay, they know that while some secrets have been finally revealed in this trip down their personal memory lanes, many more remain inside ‘The Management’s’ heads where, perhaps, for the sanity of others, they may well remain.